Fans of Anne Rice’s Vampire Chronicles series rejoiced to learn of new television adaptations that were announced, to be added by the author and her son, Christopher Rice. With her unfortunate passing, those plans are on hold. Among the announcements from the AMC network were that they were going to do a television adaptation of her most famous novel, Interview with the Vampire.

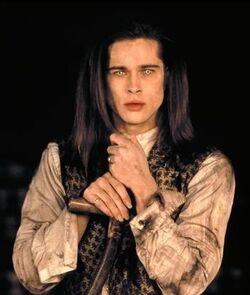

Because so much of these news items proliferate on the internet, it didn’t take long for racist trolls to voice their opposition to the casting of mixed-race actor Jacob Anderson in the role of the titular character, Louis de Pointe du Lac. Why? Because he doesn’t fit their white supremacist ideals and expectations. Go with me on this one. Yes, in the novels, Louis is a white man of Western European French descent. Yes, Brad Pitt portrayed him with brooding perfection in the 1994 film adaptation.

However, what many people may not be as familiar with is the history of les gens de couleur libre in New Orleans (“free people of colour”). Anderson, who is of mixed African and Western European ancestry, may have been considered a free man of colour if he lived in antebellum New Orleans. He may have owned a business as well as property in the French Quarter. He could also have been wealthy enough to purchase enslaved people of African descent to work on one of the plantations he inherited from his white father, more than likely an enslaver. It’s worth noting that free people of colour, particularly those who owned enslaved people, did not have the moral objections that one might think they would have to treating their own people like property, taking no pity on them, and engaging in whippings as well as other brutal punishments.

Free people of colour fundamentally thought of themselves as having all of the same privileges and rights as white people. No matter how much whites reminded them that they disagreed vociferously with this belief, free people of colour continued as they were, amassing great wealth, purchasing buildings and other properties, and buying up the finest fashions that were in vogue.

If Louis de Point du Lac were a free man of colour, he could also have purchased enslaved people from the auction block under the guise of enslavement but secretly used that as a way of freeing them.

Or he could have done none of those things.

Mixed-race individuals, usually of African and Western European descent–sometimes Native American as well–were a major part of the population of New Orleans starting in the 1700s. Despite the laws and edicts that white lawmakers instituted for Louisiana, most people disregarded them, particularly the law against miscegenation (interracial marriages between people of Western European descent with people of African or Native American descent).

Some free people of colour were enslaved first, some manumitting themselves, others set free by their masters or mistresses. In some cases, an enslaver might allow one of his enslaved “property” to buy their freedom if they paid a price high enough. White enslavers commonly had mainly forced relations with enslaved women and girls of African descent on plantations. When children came from these unions, the enslaver may have set one or more of these children free on the grounds that they were his children and that he was “making a special exception” for them. However, in most cases, the enslaver would have kept these children to sell later on, particularly lighter-skinned girls who could fetch a high price. In other instances, enslavers sold their mixed-race children to other enslavers.

Many enslavers had a high desire for–and placed great value on–lighter-skinned enslaved people, particularly girls and women who could be sold to much older white men who took them as forced mistresses. For folks wanting a more in-depth exploration of this topic and its related sub-topics, they should consult Beyond Slavery’s Shadow by Professor Warren Milteer.

In the Vampire Chronicles series books in which Louis appears, he is said to be a plantation owner in the late 1790s. He is in his early 20s when he has lost his brother (the film changed it so that he has lost his wife and child). He seeks death in whatever form it comes and is profoundly depressed.

So, what does this have to do with free people of colour?

The stratification and hierarchies of race in antebellum and Reconstruction-Era New Orleans were far more complex and intricate than one might assume. Although most free people of colour tended to be lighter-skinned, and in some cases could easily pass for white, others were darker-skinned, contrary to the assumption that only people of certain skin tones could be part of this class.

So, although it makes sense that Rice portrayed her Louis as a French-descended Creole born in the US as opposed to in France like his parents, it makes equal sense that he could have just as easily been a free man of colour.

Speaking of free men of colour, another great series of books that features a particular free man of colour, Benjamin Janvier, is A Free Man of Color by Barbra Hambly. It is the first book in a series of mysteries that centre around Monsieur Janvier and his adventures in 1830s New Orleans.

Whatever the finer points may be, and putting historical influence aside for a moment, hopefully we can all agree that when the television adaptation of Interview finally makes its way to the small screen and becomes available for viewing, we can all sink our collective fangs into it. According to AMC, the series should debut this fall (eep!)

Here is a parting image of actor Sam Reid, who plays Lestat de Lioncourt, the brash, iconic, impulsive, seductive, murderous, and about a dozen other things, vampire, one of the best of all time, looking more like a fallen than Lucifer himself.

You must be logged in to post a comment.